Archive for December, 2010

“Photography is so easy . . . Why does a pro charge so much?”

Tuesday, December 14th, 2010

Note: This article explains why pros like us charge what we charge and why we get it.

First, the long answer.

Photographers in the “ business” of photography don’t view their business as a hobby. The motivating factor is income. The average hobbyist – a nonprofessional – sees photography as an enjoyable pastime, and receiving money for their photography, although a nice addendum, is not the reason they engage in the activity. A hobbyist can be at several levels, from a novice to an accomplished photographer, but a pro has to always be at the top of his or her game to compete. After all, no professional photographer’s client wants to pay for sub-par images.

An amateur may show his shadow or reflection in the final picture, while a pro would never think of submitting such an image to the client. A nonprofessional photographer – an amateur – takes snapshots. “Click!” A pro may take a quick shot, but he or she quickly calculates variables to get the best possible shot, from the sun’s angle, to shadows, to exposure. To avoiding including as little as possible of his or her shadow so as to be less difficult to remove post-shoot. Getting closer to the ground or framing the subject through another object may not only get a more enticing image, it may as well eliminate the photographer’s shadow. Every little detail of an image is considered while shooting. Visualizing the image as a finished product, in two dimensions on a computer screen or in a print, is an essential part of the professional’s job.

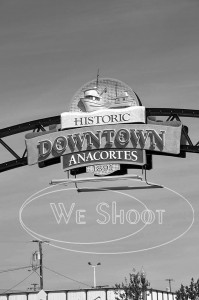

Let me provide you with an example of work we do for a particular client to help illustrate the mark of – and the necessity for – a pro. This client, an out-of-state advertising agency, commissions our work for their client (a bank), sending us to many locations a year to shoot specific subjects (and other subjects we deem suitable) in the community around their branches. From our submission, our client chooses a number of images to be displayed in each branch for which we shoot. Requirements for these shoots include high-resolution images in a vertical, black and white, gray-scale format. If our images are submitted by FTP, they can be high-res jpegs; if delivered on DVD, they will be tiffs. No horizontal or color images (not even as sample images) will be accepted, so every sample image we send has been first converted to black and white. We have done a large number of jobs for this client because we deliver what they want, what they need. They expect artistry in taking the images and artistry in executing the post-shoot processing of each of our images.

Let me lead you through the workflow on the assignments we do for this agency. With the assignment comes a list of specific things in the community to shoot. We travel to the community, some as near to our studio as one hour, some as far as a day’s drive. We arrive in the community with maps we have printed up from our research of subject matter our client has shown primary interest in, and then we drive around to locate other targets we see as appropriate for this client. Leaving before sun break may be necessary for some objects of interest, knowing that a low-sun angle may cause our shadow to appear in the image, and conversely, if we are facing the sun, flares may occur (especially with a wide-angle lens), resulting in noisy silhouettes or blown-out skies. We are sometimes asked to shoot on a deadline in the rainy season, meaning diminished shooting days and hours. While shooting in the rain with its accompanied white or gray sky (cutting contrast, for just one example) can be dealt with, mist on the lens will ruin an image and must be carefully monitored. We also don’t typically shoot higher than 400 ISO, as this usually introduces an unacceptable amount of video noise to the discerning professional eye, especially in the shadow areas, but sometimes it must be done.

A discerning professional eye also abhors low-light conditions, so a portable flash mounted on a flash bracket is a necessary part of the equipment bag. One never knows when having a little more light could come in real handy.

You may ask what’s the big deal about shooting black and white. Simply set your camera to black and white, right? Well, after some experimentation, I found that our Nikon cameras’ black and white mode still shoots the raw images in color, and the camera is merely adding a black and white filter to the image. If I take the image in b&w mode, I can remove the b&w filter in Nikon’s raw editor, Capture NX2, or if I run it through Camera Raw in Photoshop CS5, it doesn’t see the filter that was put in by my camera, at all. So, I don’t even bother shooting it in b&w in the camera. I add it later as a layer in Photoshop CS5, which gives me more options in the look of the image.

So, let’s say that I take a close-to-perfect image. What happens then? The amateur can take the memory card to a camera-store kiosk to output to disk or print – enhanced to the kiosk program’s ability. Or, the amateur can elect to work on it himself, let’s say with Photoshop Elements, a relatively inexpensive program that produces good results. Great for the amateur photographer but a program which pales in comparison to the immeasurably more professional Photoshop CS5 and the raw editing of the aforementioned Nikon Capture NX2 – both incredible programs costing – and worth – much more.

Using the raw editor, I weed out the images that are not up to the caliber I wish to present to my client. Yes, even pros have camera movement, out-of-focus and under- or overexposed images. These are discarded. During the shoot, we take several images of the same thing, one of many differences between a pro and an amateur. This backup is further enhanced by using two different cameras and, when possible, two different shooters. One camera has the long zoom (18-200mm), and the other has an ultra-wide angle zoom (10-20mm) lens. If for some reason the subject isn’t captured successfully by one photographer, it is captured by the other. Consequently, we have several versions of the same subject from which to choose the very best for the client to select from.

All images that pass muster are then further evaluated with the raw editing program. Adjustment of density (lightness and darkness). Selection of the most accurate and impressive color. Saturation. And mild sharpening. The images are then converted to tif images, labeled with our copyright and other information from the image metadata.

Another place a professional such as myself is different than an amateur is hard-drive space. Hard-drive space is a commodity to me. I buy new one-terabyte drives to replace those that fill up. None of our professional images are erased to make room for new images. All work is stored on multiple drives. There’s never enough backup. Images are lost by the client – disks are misplaced – more times than I wish to count. It’d be death for my business if all I saved an image to was one drive and I got that fateful call from a client, and had a drive failure. In the long run in terms of both time and money, it is cheaper to save an image to the hard drive in perpetuity than it is to burn it to removable media (CDs and DVDs). This, of course, adds expense to the business. But it makes me more efficient. And takes up less room in my studio.

I now take the color tif images I made in Capture NX2 and bring them up in Bridge, the sorting program that comes with Photoshop CS5. Next, I open a number of them in Photoshop, magnifying each image to 100%. Having a powerful computer system with lots of processor horsepower and ram to run these programs is of immeasurable value, increasingly necessary to the professional with a large workload. I am currently running an i7-950 processor, and 12-gigs of ram with eSata internal drives and USB 3.0 external drives, a time saver for the loading and processing of the high-res images delivered by my cameras. Again, a necessary business expense. When efficiency and high quality are needed, sparing no expense is first on a professional’s business agenda.

At 100% magnification, I scrutinize each image for imperfections. A dust mote on the sensor can have the appearance of a fuzzy “ball” in the sky, and it needs to be touched out. If a distracting shadow or reflection was also captured in an image, that will need retouching work, as well. If a building’s sides aren’t straight (a distortion caused by the lenses and the angle taken), I will bend the image to make them so, if it enhances the look. Even if our client doesn’t demand it, cigarette butts and other things that distract from a good-looking image are removed to make it a better image. Providing a client with the best – from the image samples to the finished product – is a mark of a professional.

At this point, it is time to turn the image into a psd, or Photoshop, file. I then use a “black and white adjustment layer” in Photoshop to take away the color. Oftentimes, the b&w image will look “flat,” lacking contrast. There are several software filters available in Photoshop. Years ago, when using b&w film, a photographer might use a colored filter to enhance an image. A red filter, for example, will produce a dark or black sky with white clouds. Infrared film will produce white foliage. Photoshop has filters that mimic these traits in a b&w digital image, and can be modified as well. Or I may choose to add contrast or a light or dark sky, or make a “soft-light” layer and darken or lighten some section of the image only. The image is then saved as the layered psd file in case additional changes have to be made. At this point the image is still in color with adjustment layers. Once I am happy with the image, I “flatten” all the layers to one and save it as a gray-scale tif in another folder. When all of this is accomplished (my last job with this client totaled 107 and took several days), I prepare the images for my client. I use an “action” in Photoshop to automatically save a reduced-size version of each image in another folder as a low-resolution jpeg, and then I prepare another folder for additional backup. I then bring up every image in that folder in Photoshop, and use a brush “stamp” to put our “We Shoot” watermark on every one. But I am still not done. I then make a single “zip file” of all of these images to transfer to the client by FTP or into their drop box. I advise them, usually by email, that they’re ready to see, and they unzip the file with their unzip program to see all the images. I then await their notification of the image numbers they want in final high-resolution, sending them the images on disk, via FTP, or to their drop-box.

Why does a pro charge so much? When photography is so easy? Besides the photographic and post-production time and expense involved in making a successful image, it’s more than just love of the art. It’s knowing our work will make our client successful, increase their return-on-investment, and keep them coming back for more.

And the short answer is, being a professional – being able to provide high-quality photography to a client – costs money. We fulfill a need for a client who needs high-quality images, and we need to make enough to continue to provide high-quality business to our client. It makes our client money, and it makes us money. A successful image goes a long way in helping to sustain a successful business – a professional business – for our client and this pro. A win-win for all concerned.

-Gary Silverstein

Jpeg made from unedited raw image

Jpeg of raw image after editing

Jpeg of final black and white image